Honolulu Advertiser

COMMENTARY by Cliff Slater

December 21, 2003

Content

of their character[i]: Philosophy,

not law, basis of Michigan-case ruling

Hawaii is not the only

state battling over race issues in the courts or the only one with emotions

running high and objectivity low. It is difficult to be objective when dealing

with familiar people, places and institutions. Under such circumstances the

immediacy of the disputes stirs our juices and obscures the legal principles at

play.

This is why it is

helpful to review similar contentious cases where our emotions are not so

engaged.

If we were to pick one

case that might show what is happening elsewhere in the country and what the

Supreme Justices are thinking on the subject we could do worse than to review

the recent Supreme Court decision in the Barbara Grutter affirmative action

case (and its companion, the Jennifer Gratz case). This case provides us with

valuable insights into the makeup of the Court and their thinking on race

matters.

Grutter, an applicant

denied admission to the University of Michigan Law School, sued the School in

U.S. District Court for using race as an admission factor, giving black,

Hispanic and Native American applicants[ii]

“a significantly greater chance” than Japanese, Chinese and Caucasians in

violation of the Constitution[iii]

and U.S. statutes[iv] despite

having no “compelling state interest” in doing so.[v]

For its part, the School

claimed that while race was a factor in their admission process, which was

designed to achieve a “critical mass” of “racial and ethnic diversity,”[vi]

it met the criteria formulated in earlier cases[vii]

where it had been deemed lawful to take race into account as a “plus factor,”

provided that admission policies were “narrowly tailored” and with a

“compelling government interest” in using race discrimination.

The District Court found the School’s use of race to be

unlawful.[viii]

On appeal, the Sixth U.S. Circuit court reversed the lower court’s decision.

Ms. Gutter then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld the Sixth Circuit’s findings in a narrow

5-4 decision with Justice O’Connor joining those generally regarded as the

liberals in the Court, Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, David H. Souter, Stephen

Breyer and John Paul Stevens.[ix]

The majority said, “Today, we hold that the Law School has a

compelling interest in attaining a diverse student body … Our holding today is

in keeping with our tradition of giving a degree of deference to a university’s

academic decisions, within constitutionally prescribed limits.”[x]

The facts: The Michigan Law School ranks among the Nation’s top law schools and receives more than 3,500 applications each year for a class of around 350 students. The school’s expert witness testified that a race-blind admissions system in 2000 would have admitted only 4 percent of underrepresented minority students versus the actual admission of 14.5 percent.[xi]

The issues: Judging by the court’s opinion, the three primary

questions before it were whether the State of Michigan had a “compelling state

interest” in using race discrimination, whether “critical mass” was essential

and whether the “admissions policy was “narrowly tailored.”

“Compelling interest”:

Was it compelling for Michigan to use race discrimination in the admissions

process for the school, one of the nation’s top five law schools?

While the 1964 Civil Rights Act is explicit: “No person in the United States shall, on the ground of race … be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance,”[xii] all laws are tempered by certain “compelling state interests.” For example, First Amendment free speech rights are justifiably tempered by the potential harm of crying fire in crowded theaters.

Was the admission policy that compelling? Yes, says the School, the Courts have long held

that schools have a compelling state interest in achieving diversity.

The Court’s majority

said they “struggled” with using race discrimination but said, “We

endorse [the] view that student body diversity is a compelling state interest

that can justify the use of race in university admissions.” [xiii]

But they did not make the case logically and, other than citing prior cases,

made no attempt at it.

Justice Clarence Thomas’[xiv]

response was: “Today, the Court insists on radically expanding the range of

permissible uses of race to something as trivial (by comparison) as the

assembling of a law school class. I can only presume that the majority’s

failure to justify its decision by reference to any principle arises from the

absence of any such principle.”[xv]

He asks what is Michigan’s “compelling state interest” in having an elite public law school. [xvi] He points out that five states, including Massachusetts, have no public law schools at all — let alone an elite one. He notes that it is not as though the graduates serve Michigan’s citizenry since of last year’s graduates only 16% elected to stay in Michigan. In contrast, Michigan’s only other public law school, Wayne State, had 88% of its graduates stay in the state.

He asks that if the School is so enamored of underrepresentation, it should be concerned that black women students outnumber black men students nearly 2-1, yet the school does not discriminate in favor of black men.

Justice Thomas revisited all the Court’s prior treatment of

racial classification cases and concludes that where the Court has in prior

decisions “accepted only national security, and rejected even the best

interests of a child, as a justification for racial discrimination, I conclude

that only those measures the State must take to provide a bulwark against

anarchy, or to prevent violence, will constitute a ‘pressing public necessity.’”[xvii]

“Critical mass”: Did the school also need a certain number of the underrepresented minority? Yes, said the School, and “such that underrepresented minority students do not feel isolated or like spokespersons for their race.”[xviii]

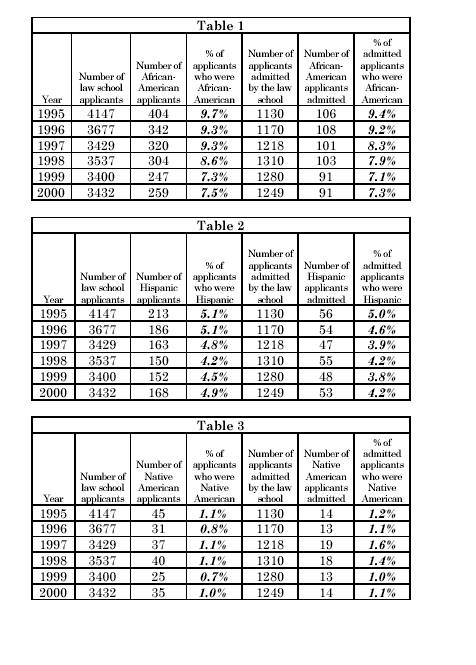

However, Chief Justice William Rehnquist pointed out that over a five-year period, the school admitted 13 to 19 Native Americans, 47 to 56 Hispanics and 91 to 108 blacks annually. He argued that, “If the Law School is admitting between 91 and 108 African-Americans in order to achieve ‘critical mass,’ thereby preventing African-American students from feeling ‘isolated or like spokespersons for their race,’ one would think that a number of the same order of magnitude would be necessary to accomplish the same purpose for Hispanics and Native Americans.” He asked why this concept was applied differently among the three groups. Thus, the School’s actions “demonstrate that its alleged goal of ‘critical mass’ is simply a sham.”[xix]

“Narrowly tailored”: Did

the school’s admissions policies meet this requirement?

The court’s majority opinion had said, “The law school’s interest is not simply to assure within its student body some specified percentage of a particular group merely because of its race or ethnic origin. … That would amount to outright racial balancing, which is patently unconstitutional.”[xx]

And the school’s director of admissions “testified that at the height of the admissions season, he would frequently consult the so-called Daily reports that kept track of the racial and ethnic composition of the class (along with other information such as residency status and gender) … to ensure that a critical mass of underrepresented minority students would be reached so as to realize the educational benefits of a diverse student body.”[xxi]

Justice Rehnquist showed the table below demonstrating a direct correlation between the percentage of each type of minority applicant applying for admission and the percentage of those actually admitted.[xxii] He termed the process “a naked effort to achieve racial balancing.”

Justice Scalia called it, “a sham to cover a scheme of racially proportionate admissions” adding that, “the Constitution proscribes government discrimination on the basis of race, and state-provided education is no exception.”[xxiii]

He further criticized,

“universities that talk the talk of multiculturalism and racial diversity in

the courts but walk the walk of tribalism and racial segregation on their

campuses — through minority-only student organizations, separate minority

housing opportunities, separate minority student centers, even separate

minority-only graduation ceremonies.”[xxiv]

Then Justice Thomas turned to the use of race discrimination as a policy: “What lies beneath the court’s decision today are the benighted notions that one can tell when racial discrimination benefits (rather than hurts) minority groups and that racial discrimination is necessary to remedy general societal ills.”[xxv]

He quoted a segment of a Frederick Douglas speech of 1865:

“The American people have always been anxious to know what they shall do with us. . . . I have had but one answer from the beginning. Do nothing with us! Your doing with us has already played the mischief with us. Do nothing with us! If the apples will not remain on the tree of their own strength, if they are worm-eaten at the core, if they are early ripe and disposed to fall, let them fall! . . . And if the negro cannot stand on his own legs, let him fall also. All I ask is, give him a chance to stand on his own legs! Let him alone! . . . [Y]our interference is doing him positive injury.”[xxvi]

Justice Thomas observed that:

- “The

Constitution abhors classifications based on race, not only because those

classifications can harm favored races or are based on illegitimate

motives, but also because every time the government places citizens on

racial registers and makes race relevant to the provision of burdens or

benefits, it demeans us all.”[xxvii]

- “It must be remembered that the law school’s

racial discrimination does nothing for those too poor or uneducated to

participate in elite higher education and therefore presents only an

illusory solution to the challenges facing our Nation.”[xxviii]

- And quotes author and commentator Thomas Sowell: “Even if most minority students are able to meet the normal standards at the ‘average’ range of colleges and universities, the systematic mismatching of minority students begun at the top can mean that such students are generally overmatched throughout all levels of higher education.”[xxix]

- He discusses at length the harm that these programs “stamp minorities with a badge of inferiority” and that because some blacks are admitted only through racial discrimination that all are tarred as undeserving.

The decision: It was

what the Economist called “tortuously reasoned” resulting in a “a legal

fudge.”[xxx]

In short, the majority

decision was one by philosophy rather than by the law. From this it would

appear that Hawaii cases favoring race-based actions may prevail — but it will

depend on which Supreme Court faction prevails.

This column is extensively footnoted at www.lava.net/cslater

Footnotes:

[i] “I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Delivered on the steps at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. on August 28, 1963. Source: Martin Luther King, Jr: The Peaceful Warrior, Pocket Books, NY 1968

[ii] “…the court uses the terms “minorities,” “minority groups,” and “underrepresented minorities” interchangeably in this opinion to refer to African American, Native American, Mexican American and mainland Puerto Rican students, as these are identified in University of Michigan Law School documents as the groups which receive special attention in the admissions process.” Opinion of U.S. District Court. http://supreme.lp.findlaw.com/supreme_court/decisions/lower_court/97cv75928.pdf

[iii] U.S. Constitution, Amendment XIV. “Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the state wherein they reside. No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” http://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/constitution.amendmentxiv.html

[iv]

Civil Rights Act of

1964. Title VI. Sec. 601. “No person in the United States shall, on the

ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in,

be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program

or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” (Pub. L. 88-352, title

VI, Sec. 601, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 252.) http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/cor/coord/titlevistat.htm

Title 42, Chapter 21, Subchapter I, Sec. 1981. - Equal rights under the law

“(a) Statement of equal rights — All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.” http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/42/1981.html

[vi] Grutter. Opinion of the Court. P. 3. “with special reference to the inclusion of students from groups which have been historically discriminated against …”

[vii] Formulated in the 1978 Supreme Court Bakke decision regarding UC-Davis Medical School admission policies. Regents of Univ. of Cal. v. Bakke, 438 U. S. 265 (1978)

[viii] Michigan District Court decision. http://supreme.lp.findlaw.com/supreme_court/decisions/lower_court/97cv75928.pdf

[ix] CNN questions Law Professor Michael Dorf on Supreme Court makeup: “Michael Dorf: The court is divided into roughly three camps. There are three solid conservatives: Chief Justice William Rehnquist, Associate Justice Antonin Scalia, and Associate Justice Clarence Thomas. There are four moderate-to-liberals: Associate Justices John Paul Stevens, David Souter, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer. And then there are the swing votes: Associate Justices Sandra Day O'Connor and Anthony Kennedy. O'Connor and Kennedy tend to vote with the conservatives in cases involving state-federal conflicts. They favor the states over Congress. But O'Connor and Kennedy often vote with the moderate-to-liberals on questions of individual rights.” http://www.cnn.com/2000/LAW/07/transcripts/dorf.scotus.fl.07.27/index.html

[xii] The 1964 Civil Rights Act. Title VI. Sec. 601.

[xiii] Grutter. Opinion of the Court. P.13. They also said, “Today, we hold that the Law School has a compelling interest in attaining a diverse student body … Our scrutiny of the interest asserted by the Law School is no less strict for taking into account complex educational judgments in an area that lies primarily within the expertise of the university. Our holding today is in keeping with our tradition of giving a degree of deference to a university’s academic decisions, within constitutionally prescribed limits.” Opinion of the Court. P. 16.

[xiv] Justices Thomas and Scalia both consider themselves to be textualists. “To be a textualist in good standing, one need not be too dull to perceive the broader social purposes that a statute is designed, or could be designed, to serve; or too hide-bound to realize that new times require new laws. One need only hold the belief that judges have no authority to pursue those broader purposes or write those new laws.” Scalia, Antonin. A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law. Princeton University Press. 1997. P. 23.

“Words do have a limited range of meaning, and no interpretation that goes beyond that range is permissible.” Scalia, Antonin. A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law. Princeton University Press. 1997. P. 24.

[xxii]

See table .

[xxvi] What the Black Man Wants: An Address Delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, on 26 January 1865, reprinted in 4 The Frederick Douglass Papers 59, 68 (J. Blassingame & J. McKivigan eds. 1991)

[xxix] Sowell, Thomas. Race and Culture. 1994. pp. 176-7.